How to Make Software Like Pablo Picasso

Who would have thought that a cubist's minimalism could teach us something about software design.

I remember the first time I saw Pablo Picasso's “Bull” lithograph series.

I was staying in Santiago, Chile, and there was a public exhibition of the famous Cubist's work. Many of his amazing paintings, drawings, sculptures, and lithographs were on display.

Even though I enjoyed seeing all Picasso's work, there was one exhibit in particular that made a lasting impression and has stuck with me all these years: the “Bull” series of lithographs.

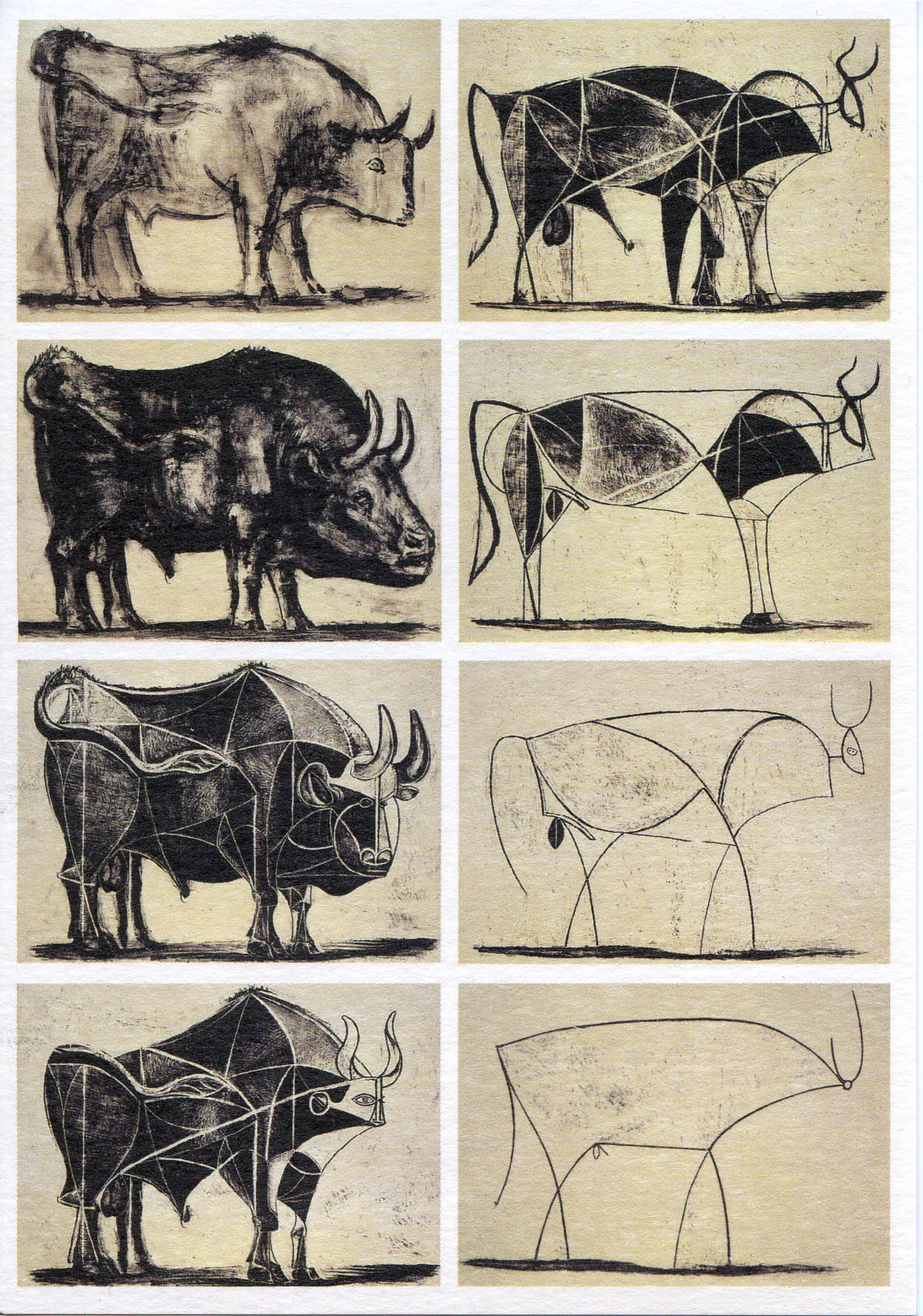

What really struck me about the “Bull” series was that Picasso had seemed to work backwards. Starting with a realistic sketch that any artist would have been proud of, he removed some elements and abstracted others until all that was left was a simple line drawing.

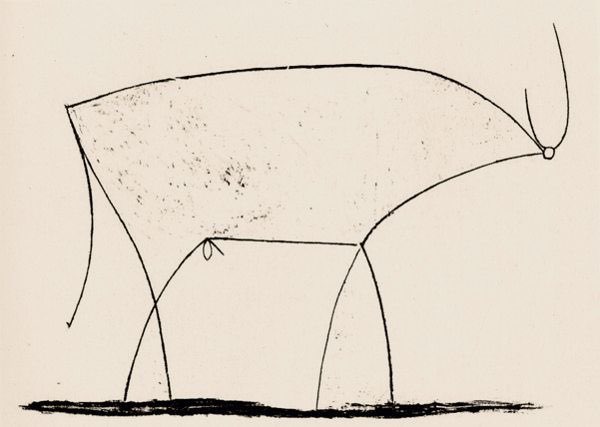

But even though it consisted of only seven or eight lines, the final drawing still conveyed the impression of the bull. He had removed everything except that which was absolutely essential to conveying the message of “this is a bull”.

It was the opposite of everything I had learned about art up to that time.

Art, I thought, was created by progressively adding to an image to make it better, prettier, and more realistic. Picasso had turned this on its head and showed me that art could also be created by removing detail to reveal the minimum amount of information that is required to convey an image.

Pablo Picasso created “Bull” by progressively refactoring the image from a realistic sketch into a completely abstract line drawing that, though it lacks detail, still evokes the essence and form of a bull.

Like art, software development is not a linear process. It is not like moving a pile of stones. If it were, we could count the number of tasks to be done and multiply by how much time each task takes and know exactly how long something will take to build.

Like art, software development is not a linear process. It is not like moving a pile of stones. https://t.co/Uogc4EUZxa pic.twitter.com/rG3FJidRxC

— Booster Stage (@Booster_Stage) December 5, 2017

Instead, software development is more like drawing a sketch. A certain minimum number of lines are required in order for an image to become recognizable. But like Picasso, an experienced developer is able to abstract and reduce a feature down to its essential simplicity by building only that which is absolutely essential to the feature's functionality.

Unlike Picasso, however, the software developer works in the opposite order: the bare abstraction comes first, and layers of complexity are added after each feature is tested and proven.

Minimalism is not only for cubists

When creating software there is a strong temptation to build the whole package. Every feature seems important, and it probably is.

But there's a problem: it's not humanly possible to create a complete software project in one go-round. Without proper prioritization, the project becomes too cumbersome, and the launch date becomes a receding deadline.

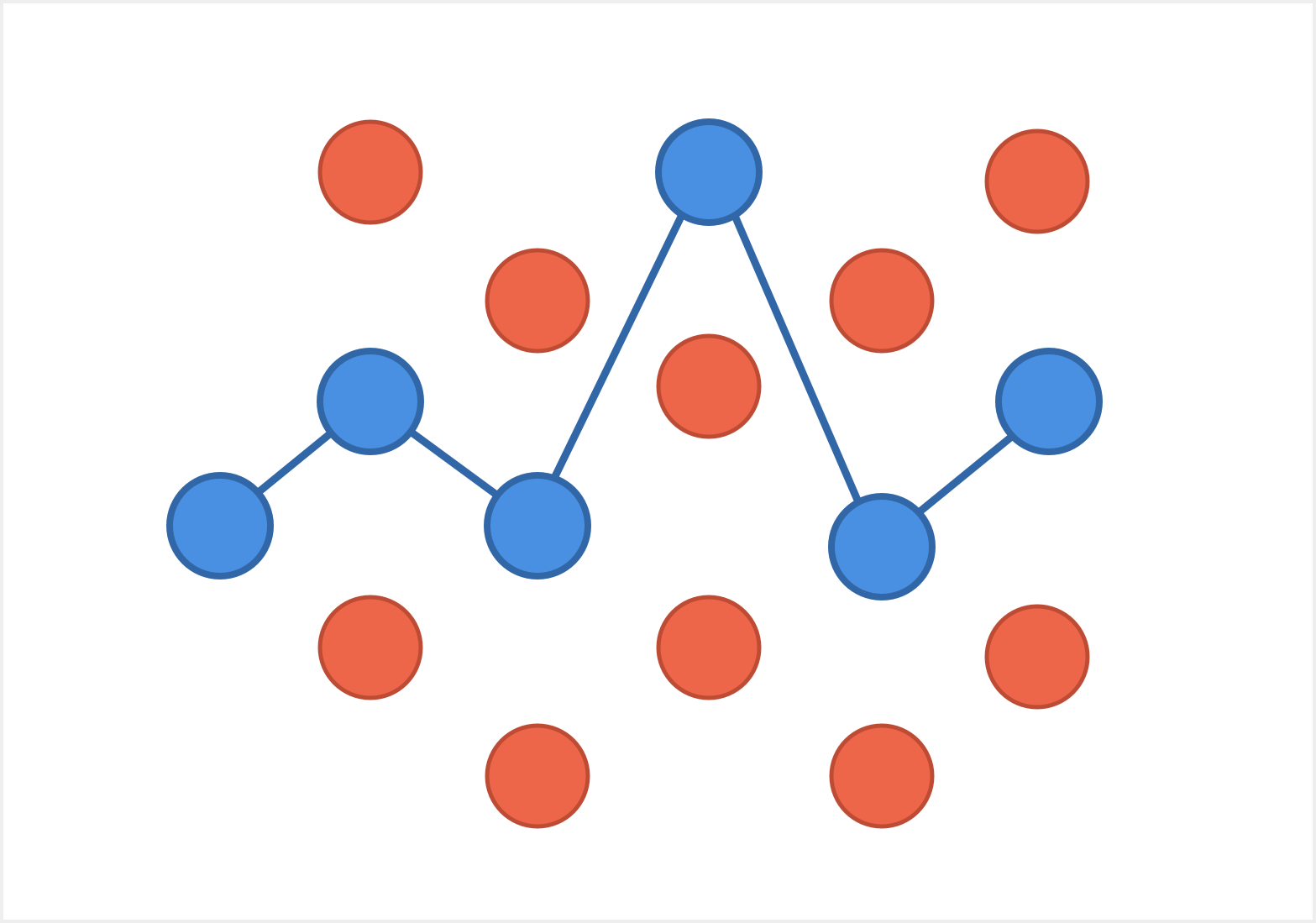

Throwing additional resources at a project doesn't help either. Any project manager will tell you that doubling team size does not translate to halving the timeline.

What we need is a reliable way to prioritize features. But without a strong prioritization framework it's easy to get muddled in the details. That's where the Critical Path comes in.

The Critical Path

A Critical Path is a list of the fewest number of features that have to be built in order to validate that you're building the right product.

When you have a large list of things to do, a critical path helps to focus the list on just those things that materially advance the goals of the project. The Critical Path does this while recognizing that other tasks are important also, and will be done in due time.

The question that the Critical Path designer asks is not “how much can we fit in to the first version and still hit our deadline”; it's “how little can we build to validate our ideas at this stage”.

Hiten Shah, in his excellent newsletter, says that it's “the fastest path to critical learnings to reduce engineering time from months to days”. It's by no means the “easy” path—in fact in Hiten's case they spent quite a bit of time up front researching and planning instead of diving into code. Resisting the temptation to build the product of their dreams wasn't the easiest choice.

The second path - the one we took - meant spending much more time and effort up front before writing a single line of code. It meant pruning all our wildest dreams to make sure we built only the one functionality that mattered to make this product a success. This path meant focusing on learning and experimentation. Having a working prototype in a matter of weeks (or even days). Talking to users. And then building more. Another round of learning and testing (heck, more like ten rounds). And then building even more yet again.

Minimalism is Risk Mitigation

This minimalism isn't grounded in laziness. Instead it's a form of risk mitigation.

Writing software is inherently risky. Not “wingsuit base jumping into the open door of a flying airplane risky”, but risky.

Creating software is risky because it always involves using scarce resources, whether that's money or time, or both. Even if you're doing it yourself in your own spare time, you're using time that you could have spent elsewhere. If your project fails, you'll have wasted time.

If there's money on the line, the risk is even greater. Nobody likes to waste money. It's pretty much the worst feeling ever. (The only thing that's worse than losing money is wasting more money due to the sunk cost fallacy.)

Focusing on the Critical Path—the least we must do—forces us to think like Picasso. To trim out all the excess, and remove everything that doesn't materially add to the actual delivery of our desired result.

How to find your critical path

Start with a buyer persona. Before you can build a product for someone, you have to know who “they” are. A buyer persona is a detailed description of the person who will be buying your product. Notice that I said “person” and not “company”. Even if you’re designing a B2B (Business to Business) product and not B2C (Business to Consumer), it is people who buy products, not companies. So if your buyer persona represents a company, that’s part of their persona.

The buyer persona should list every attribute that you can think of, including demographic information, details about their job, problems they may be experiencing at work that may lead them to seek out a solution like your product, etc. When it comes to buyer personas, it’s almost impossible to be too detailed. Oh, you can (and should) have multiple buyer personas.

If you’re new to buyer personas, a great place to start is The Crucial Steps to Actually Quantifying Your Customer Personas on the Price Intelligently blog.

A Critical Path is a list of the fewest number of features that have to be built in order to validate that you're building the right product. https://t.co/MotYQbLE0f

— Booster Stage (@Booster_Stage) December 5, 2017

Next, list all the features your app will have. At this stage it’s helpful to pretend like you’re writing the marketing copy for your website. How would you explain this feature to a potential buyer, without giving overwhelming detail.

Now comes the hard part: it’s time to eliminate features. For each feature, refer to your buyer personas: would they stop paying for the product if it lacked this feature?

The point here isn’t to prioritize features, so much as it is to minimize your risk exposure by whittling down your MVP to the smallest possible set of features. Remember, features that don’t make it to the critical path are not necessarily eliminated from the app. Instead they are simply deferred until a future version.

With your critical path in hand you are in a position to begin the Build-Code-Learn cycle with confidence that you’re building something lean and testable, that’s exactly what your customers want.